It is the pride of German manufacturing, it is a model of sports luxury car brand, it is the dream car of countless men and women, it officially entered the century-old car company club this year, it is BMW! Yes, BMW today is one of the most successful luxury car brands, with good sales and reputation around the world. However, it has not always been smooth sailing in its 100-year history. During the most difficult times, BMW even became the “BMW Woodware Factory” and the “BMW Cookware Factory”. Today, let us review the ups and downs of BMW’s century-old development history.

Brand traceability

If you look at the list of car brands, you will find that most of the names of foreign brands are names of people. Whether it is Germany’s Mercedes-Benz, the United States’ Ford or Japan’s Toyota, their brand names are all derived from the surname of the founder. So why is today’s protagonist BMW called “Bayerische Motoren Werke”? In fact, this is related to its “rich” merger history. Let me explain it slowly.

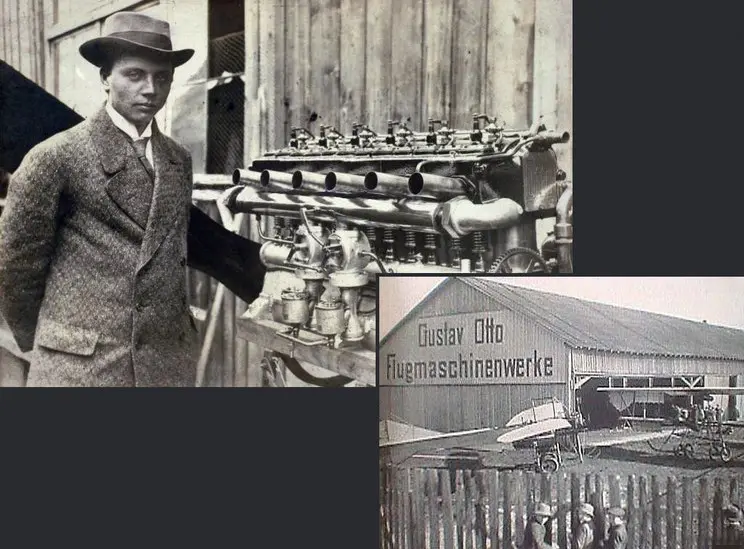

The history of BMW can be traced back to the early 20th century with two companies: Rapp Motor Works and Gustav Otto Aircraft Company, both of which bear the names of their founders. The founder of Gustav Otto Aircraft Company, Otto, was the son of the renowned inventor of the internal combustion engine, Nikolaus Otto. If you are not familiar with this person, you may have heard of the Otto cycle, which is named after Nikolaus Otto.

In 1910, Gustav Otto founded an aircraft training school and began manufacturing aircraft. Otto’s aircraft workshop was officially renamed Gustav Otto Aircraft Manufacturing Company in 1913. After several moves, it was finally located on Lerchenauer Street in Munich. Gustav Otto inherited his father’s talent in mechanics. After continuous development, Otto’s aircraft manufacturing company has become the main supplier of the Bavarian Royal Air Force. At this time, World War I broke out. The Otto company, which produced aircraft, was supposed to be a great success with military orders. However, it was in trouble because of some thorny quality problems.

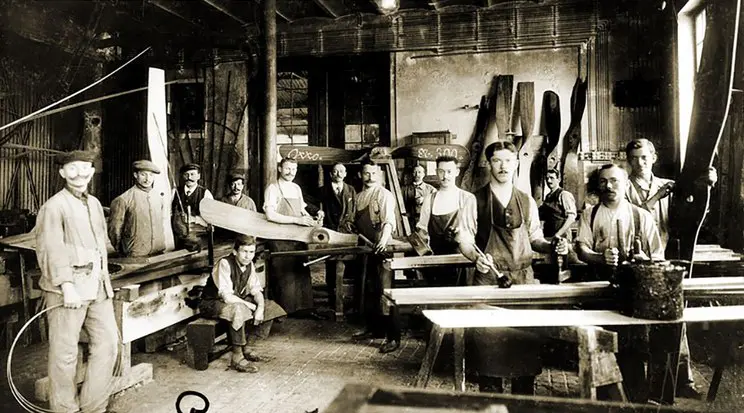

Gustav Otto ultimately failed to solve these problems, so the company was acquired by a consortium (composed of MAN and some banks) and reorganized into BFW (Bayerische Flugzeugwerke, Bavarian Aircraft Manufacturing Company) on March 7, 1916. BFW discovered that Otto’s quality problems stemmed from product accuracy, so it solved the problem by reforming the organizational structure and strengthening quality monitoring. Thereafter, BFW developed rapidly as World War I progressed. Within a few months, it grew into a factory with 3,000 workers and a monthly production capacity of 100 aircraft, thus becoming the largest aircraft manufacturer in Bavaria.

The rapid development of BFW came to a halt with the end of World War I. The Treaty of Versailles stipulated that Germany could not have an air force, and at that time the civil aviation market was still in its infancy. In other words, Germany was unlikely to have customers for airplanes, essentially condemning the German aircraft manufacturer to death. However, BFW did not accept this “verdict.” In order to survive, it began to switch to making furniture. This was because at the time, most aircraft were made of wood, and when the war ended, BFW still had enough wood in its factories to produce 200 aircraft. So, BFW transformed into a furniture factory, using its equipment to process this batch of wood into furniture and cabinets to sell on the market.

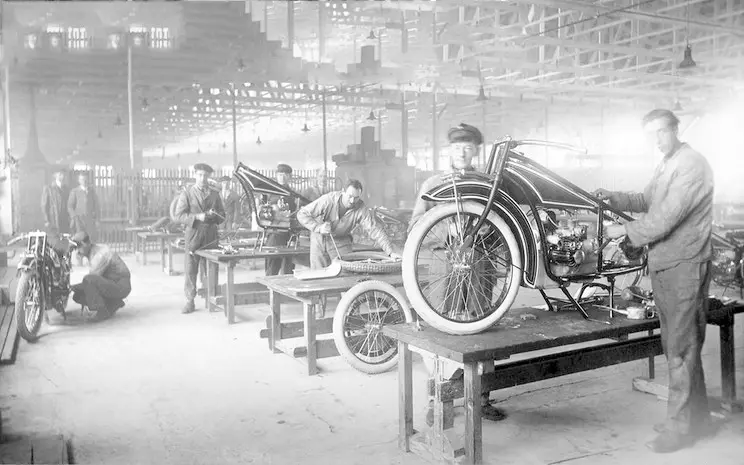

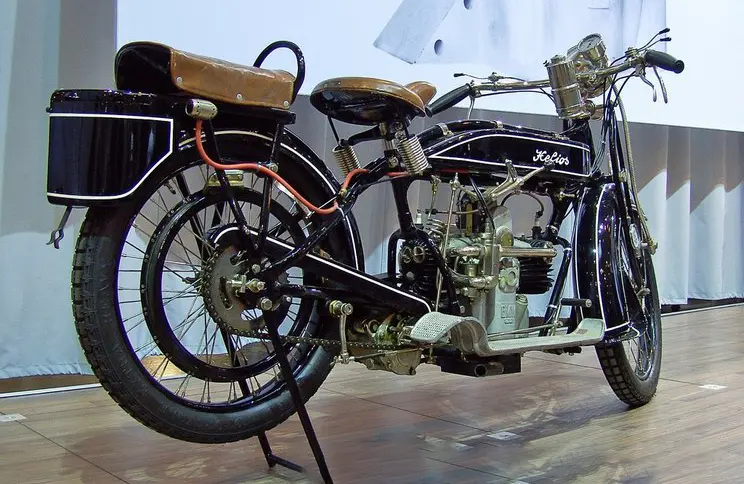

Apart from furniture, BFW began producing motorized bicycles and motorcycles in 1921. One of their motorcycles, named Helios (the sun god), was equipped with a 494cc flat-twin engine. Although BFW managed to survive with these products, it was far from reaching its wartime scale. Its factories gradually deteriorated, and the machinery became increasingly outdated. While most people saw its decline, those knowledgeable in investments saw an opportunity: Austrian financier Camillo Castiglioni (a key figure, remember this name) completed the acquisition of all BFW shares from the fall of 1921 to the spring of 1922.

Let’s start by talking about another important company – the Rapp Motor Works. Rapp was founded by Karl Rapp in 1913, and its factory was located near the Gustav Otto Aircraft Company. It was established there because Rapp’s main business was to provide four-cylinder aircraft engines for the aircraft company. Subsequently, it also received an order from the Austrian company Austro-Daimler to manufacture more advanced V12 aircraft engines as a subcontractor.

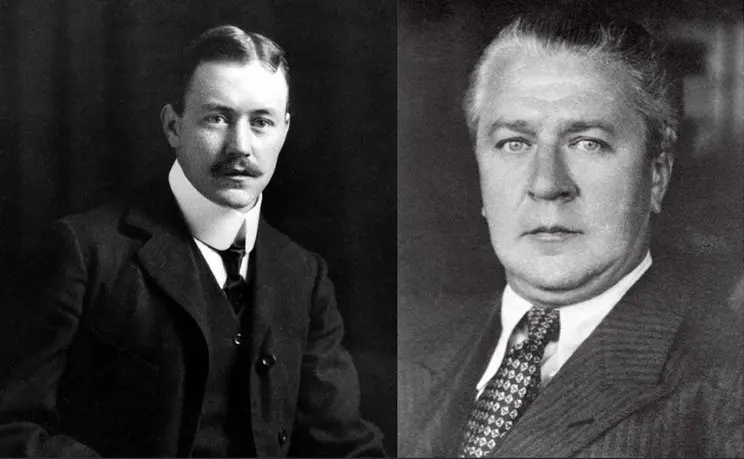

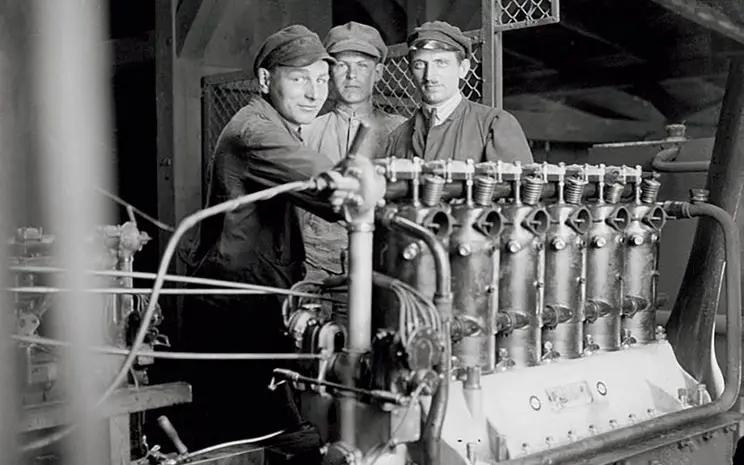

At that time, Austria sent Franz Josef Popp to Munich to oversee the product quality at Rapp. Popp did not confine himself to the role of an observer; he actively involved himself in the management of Rapp. In 1916, he introduced designer Max Friz to the company and actively advocated for his interests, knowing that Rapp needed outstanding designers like Friz. Friz did not disappoint Popp; within a few months of joining, he developed the Type III engine, based on Rapp’s old products. The subsequent Type IIIa engine represented a significant improvement over its predecessor.

Friz made several innovations in the Type IIIa engine, the most important of which was the adoption of a revolutionary carburetor. This improvement allowed the engine to deliver its full power even at high altitudes, making it the most outstanding aircraft engine in Germany at that time. The German military Fokker D.VII fighter powered by this engine greatly shocked the Allied forces, to the extent that after the war, the Allies specifically demanded that Germany should not retain a single Fokker D.VII aircraft.

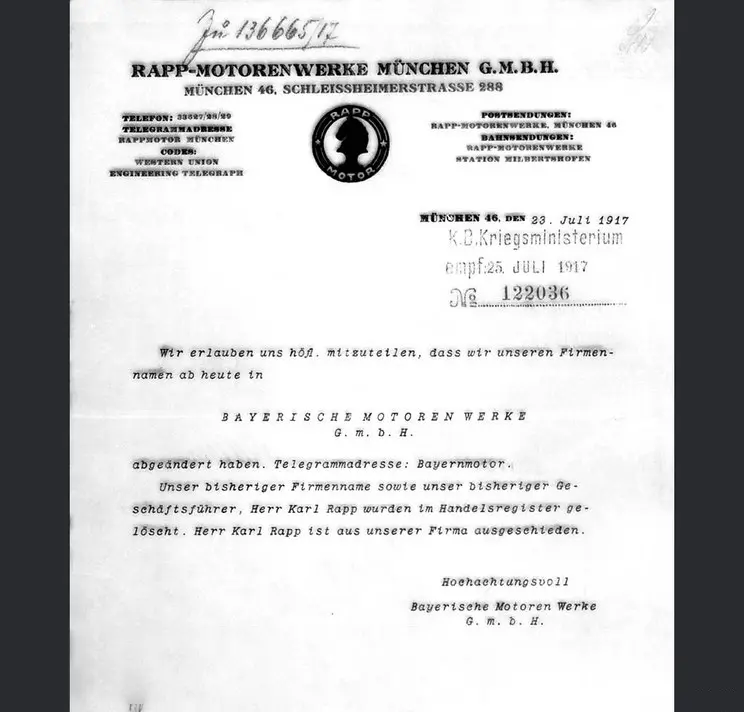

In 1917, Rapp company underwent a major personnel change, with Max Friz appointed as head of the research and development department, and Franz Josef Popp elected as the company’s general manager, while founder Karl Rapp withdrew from the company’s operations. On July 21 of the same year, Rapp company was officially renamed Bavarian Motor Works Limited (Bayerische Motorenwerke GmbH, BMW GmbH), marking the first appearance of the name BMW. Consequently, Rapp’s Type IIIa engine was also renamed BMW IIIa.

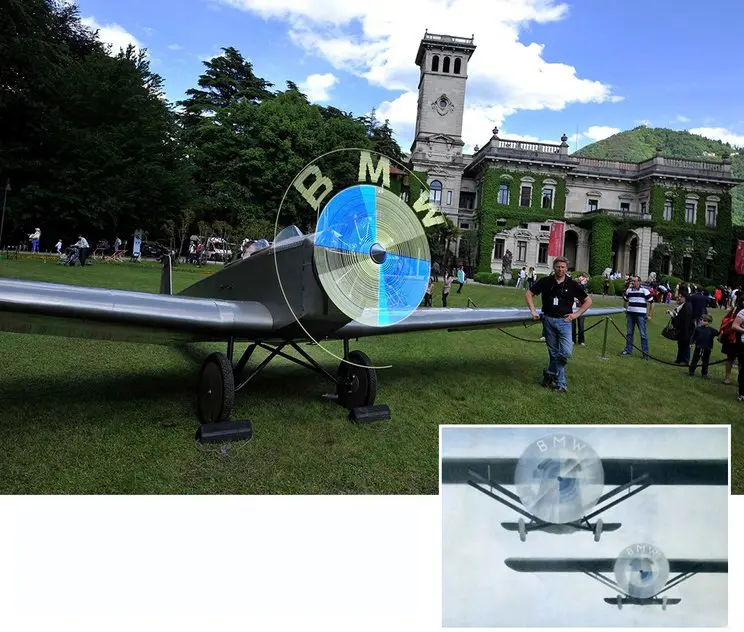

With the company’s renaming, BMW also introduced its new logo in the same year. This logo actually evolved from the old Rapp company logo, using the same black circle, but with the “RAPP MOTOR” inscription replaced by “BMW,” and the interior pattern changed from a horse’s head to the blue and white checkered pattern derived from the Bavarian flag. By the late 1920s, the circular blue and white checks in the BMW logo had a new interpretation in the company’s advertising—a spinning propeller.

The first crisis: the dilemma after World War I

During the war, BMW (hereinafter referred to as “BMW”) experienced significant growth, primarily due to government funding and guarantees under the wartime economic system. As the war continued, the war departments of Bavaria and Prussia (at that time, both Bavaria and Prussia were small kingdoms within the German Empire with certain internal powers) sought to cease endless support for the company and encouraged BMW to undergo a transformation into a joint-stock company.

On August 13, 1918, Bayerische Motoren Werke Aktiengesellschaft (BMW AG) was officially registered, inheriting all the equipment, orders, and workers of Bayerische Motorenwerke GmbH (BMW GmbH). The new company had a total capital of 1.2 million marks, with the majority held by Bavarian merchants or banks, while one-third belonged to the Austrian financier Camillo Castiglioni (the same individual mentioned earlier in the acquisition of BFW).

The First World War officially ended in November 1918. The restrictions on the German aviation industry in the Treaty of Versailles also spelled doom for BMW, as its sole product at that time was the BMW IIIa aircraft engine. This product, which had been in high demand during the war, suddenly became obsolete overnight. Adding to BMW’s woes, the post-war German government established a “Central Restitution Office” to ensure economic stability. This committee demanded the immediate closure of BMW’s factories, citing severe resource shortages in Germany. Precious coal was needed for heating, and essential metals had to be prioritized for the production of consumer goods.

After a three-month shutdown, BMW finally received permission to resume operations in February 1919. The managing director, Popp, immediately urged the design department to work intensively so that the company could produce civilian products. Initially, BMW, like BFW, was somewhat opportunistic, using the aluminum production equipment and leftover materials from aircraft engine manufacturing to produce aluminum and designing multiple engines for motorcycles, cars, and boats. Initially, BMW also resumed the production of aircraft engines on a small scale. However, all production related to air force equipment in Germany was harshly prohibited, plunging BMW into deep trouble once again.

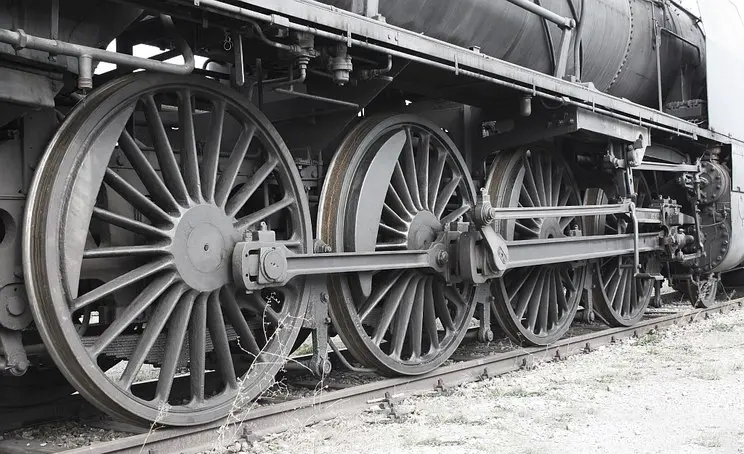

On June 18, 1919, BMW secured a lifesaving contract: it was authorized to produce railway braking systems developed by Knorr-Bremse in Berlin, with a 10-year term. This collaboration, which saved BMW from bankruptcy, was also made possible thanks to the Bavarian government. At the time, the government announced its intention to restore its own train vehicles to revive railway transportation. If Knorr-Bremse could produce in Bavaria, the government would consider purchasing its products.

The railway brake manufacturing business was far more successful than the original civilian engine production. Starting from the summer of 1919, BMW directed most of its production resources towards brake systems. While this venture brought profits to BMW, shareholders felt uncertain about the company’s future. Financial speculator Camillo Castiglioni, known for his speculative skills, began to buy up shares. As the primary shareholder of BMW, he successfully acquired all other shareholders’ stakes, becoming the sole owner of BMW.

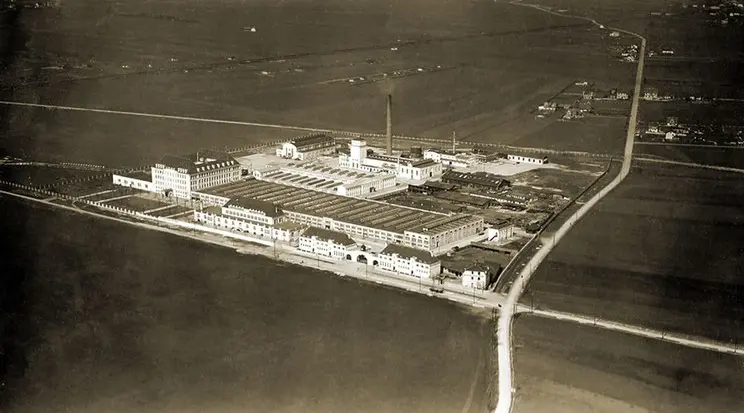

Camillo Castiglioni did not intend to hold onto this railway components factory for the long term. Instead, he sold BMW to Knorr-Bremse. Under Knorr-Bremse’s leadership, BMW indeed experienced significant growth. By 1921, BMW had 1800 employees, compared to just 800 at the end of 1918. However, this growth came at a cost. BMW had now become a full-fledged railway components factory, completely abandoning its once proud core business of aircraft engine manufacturing.

Do you remember when I mentioned earlier that Camillo Castiglioni bought all the shares of BFW at the bottom in the spring of 1922? Well, the story finally continues. After acquiring BFW, Castiglioni set his sights on BMW, but this time, he didn’t want the whole company. He publicly announced his intention to start his own engine company and began to negotiate with Knorr-Bremse to purchase the blueprints, patents, and equipment for BMW’s aircraft engines, as well as the BMW name, trademark, and several key employees, including chief designer Max Friz and general manager Franz Josef Popp.

On May 20, 1922, Castiglioni obtained everything he wanted for the price of 75 million marks (the remaining part of BMW became a subsidiary of Knorr-Bremse, and thus was no longer relevant to this story). Since he didn’t purchase BMW’s factory buildings, Castiglioni arranged for BMW’s production facilities and headquarters to be located within BFW’s factories, merging the two into the new BMW company. As a result, the official founding date of BMW is now recognized as March 7, 1916, the date of BFW’s establishment. The new BMW company’s headquarters were situated at the former site of Gustav Otto’s Otto aircraft manufacturing company, located at 76 Lerchenauer Strasse in Munich.

The first BMW-branded motorcycle, the R32, was released in September 1923. However, the company’s involvement with motorcycles dates back even earlier. In 1919, BMW developed a horizontally opposed twin-cylinder engine with the codename M2B15 for the Nuremberg-based Victoria company. This engine had a displacement of 494cc and produced a maximum power of 6.5 horsepower. Initially, BMW positioned the M2B15 as a portable industrial engine, but it was later found to be more suitable for powering motorcycles. Consequently, the Victoria company installed it in their first motorcycle, the KR 1.

In 1921, BFW introduced a motorcycle called the Helios, which actually used the same BMW M2B15 engine. After the merger of BMW and BFW, the general manager Franz Josef Popp decided to venture into motorcycle manufacturing. He tasked the head of the design department, Max Friz, with evaluating BFW’s motorcycle. After a thorough analysis, Friz came to his own conclusion: the best course of action for the Helios motorcycle was to throw it into the river. Friz specifically pointed out that the major issue with the Helios lay in its layout, as the longitudinal twin-cylinder engine configuration severely impacted the cooling of the rear cylinder.

Given the inherent flaws of the Helios motorcycle, Popp and Friz developed two plans: a short-term plan to address the issues with the Helios in order to improve sales, and a long-term plan to completely resolve these issues by creating an entirely new BMW motorcycle from scratch. The result of this new design was the BMW R32 motorcycle, which made its official debut at the Berlin Motor Show in September 1923. Upon its release, it garnered unanimous recognition from experts, the media, and consumers. It can be said that the R32 introduced the world to the fact that BMW was not only adept at manufacturing aircraft engines but also excelled in the production of motorcycles.

The M2B33 engine used in the R32 motorcycle is also a 494cc horizontally opposed twin-cylinder engine, with its maximum power increased to 8.5 horsepower. With this engine, the BMW R32 motorcycle could reach a top speed of 95 km/h. One notable difference from previous designs is that the “boxer” engine of the R32 adopted a transverse layout, significantly improving its air-cooling efficiency. Additionally, the motorcycle featured an important characteristic: the use of a driveshaft instead of a chain, a design element that has become a classic feature of BMW motorcycles along with the “boxer” engine.

The BMW R32 motorcycle boasted excellent performance, affordability, and reliable quality. Additionally, it offered good fuel efficiency, encompassing all the qualities expected of a successful vehicle model. Naturally, the market responded favorably, prompting BMW to introduce a variety of motorcycle models such as the R37, R39, R42, and R57. While these models continued to make significant strides in the market, they also achieved impressive results on the racing circuit. BMW secured the championship in all 500cc motorcycle racing events in Germany from 1924 to 1929. What was once a “side mission” for BFW had evolved into a significant source of profit for BMW in the 1920s.

The idiom ‘Delongwangshu’ carries a negative connotation, but for the development of a company, it is an important advantage. The success of motorcycles led BMW to further set its sights on the automotive industry. Prior to 1924, BMW had already begun the design and development of automobiles. Chief designer Friz, along with another designer, Dürrwächter, who was recruited from Mercedes, collaborated to design BMW’s first prototype car in 1925. Additionally, in the 1920s, BMW also produced several two-cylinder or four-cylinder engines for some agricultural vehicles.

At this point, nearly 40 years had passed since the birth and development of the automobile. For the engine company that had just recently emerged from hardship, designing a car was no easy feat. As a result, BMW decided to take a shortcut. In 1928, it acquired the Automobilwerk Eisenach company, thereby obtaining its sole product—the small family car known as the Dixi DA-1 3/15 PS. In reality, the Dixi car was also a “shortcut” for the Automobilwerk Eisenach company: due to poor sales of its own products, Eisenach had acquired a production license for the Austin 7 car from the British company Austin in 1927.

Domestic friends may not be familiar with the Austin 7, but it is actually a very important model in British automotive history. Some say that the impact of the Austin 7 on the British automotive industry is as significant as the Ford Model T was for the United States. The influence of the Austin 7 is not limited to the UK; its impact extends globally. Two renowned car companies began their automotive journey by producing the Austin 7 under license. One of them is our main focus today, BMW, and the other is the distant Eastern company, Nissan.

After acquiring Eisenach, BMW inherited the production rights for the Austin 7. Subsequently, it simply replaced the badge of the Dixi 3/15 PS DA-1 with its own “blue sky and white clouds” emblem, and thus, the first mass-produced car under the BMW brand was born. Initially, BMW retained the “Dixi” name, naming its first model the BMW Dixi 3/15 PS DA-1. However, the slightly modified model introduced in 1929 dropped the “Dixi” name and was directly named the BMW 3/15 PS DA-2.

The BMW 3/15 series’ DA-2 model was launched in April 1929. Its most significant change compared to its predecessor was that all four wheels were equipped with braking systems, whereas the DA-1 only had brakes on the two rear wheels. Subsequently, in 1930, BMW introduced the 3/15 PS DA-3 Wartburg, a sports car that unfortunately arrived at an inopportune time. Due to the impact of the Great Depression, the German economy came to a standstill, and the DA-3 had to be discontinued just one year after its launch, with only 150 units sold. As BMW’s earliest car series, any innovation within the 3/15 line could be considered a “first” for the brand. For instance, the DA-3 PS Wartburg was BMW’s first sports car, while the subsequent replacement model, the DA-4, introduced in 1931, became BMW’s first car equipped with independent front suspension due to the upgrade to independent suspension.